Welcome

To Classic

CU

Welcome

To Classic

CU

Classic CU is a part of the CUBuffs.com network. Brought to you by the University of Colorado Athletic Department and the Univeristy of Colorado Heritage Center, ClassicCU.com will feature top teams, players and athletes, and events and moments from CU's rich tradition of excellence.

The Right Thing

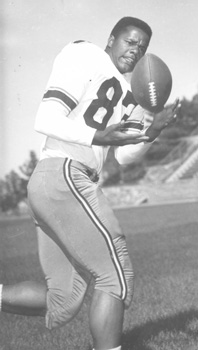

CU Athletic Hall of Famer John Wooten CU Athletic Hall of Famer John Wooten |

When ‘Shoulder to Shoulder’ were more than words in the CU fight song

Originally published in Buffalo Sports News magazine.

By Larry Zimmer

Buffalo Sports News

Two Colorado football pioneers are not able to tell this story without being reduced to tears. That’s how emotional is the history of the 1956 and 1961 Colorado Buffaloes — two teams, five years apart, but forever linked. It is a story that is familiar to only a few. Some involved have been reluctant to address it, but it’s time the true story is told.

Bowl games have become fairly common for the Colorado Buffaloes, but 52 years ago, when the 1956 Buffs qualified as the Big Seven Conference’s representative in the Orange Bowl, it was only the second bowl invitation in CU history. The first was all the way back in the 1937 season, when Byron “Whizzer” White led the Buffaloes to a Cotton Bowl berth against the Rice Owls. The 1937 Colorado team did not face the challenges presented to the 1956 team, though. The issue of race did not enter the game. Both Colorado and Rice fielded teams made up entirely of white players.

When Colorado Coach Dal Ward made the decision to recruit black players, he signed a 6-0, 210-pound end (as they called them on those days), Frank Clarke, from Beloit, Wis., who had gained notice at Trinidad Junior College in southern Colorado. The year was 1955. Technically, Clarke was the second African-American to wear a CU football uniform. A fullback named Clifford Evans was on the freshman team in 1929, but didn’t play varsity football.

The following year, Ward recruited and signed 6-2, 230-pound offensive guard John Wooten from Carlsbad, N.M. Wooten would win All-America honors before his career was finished. He also starred in the National Football League for 10 years with the Cleveland Browns and Washington Redskins. He gained national recognition as the pulling guard who blocked for the great Jim Brown at Cleveland.

Clarke also had a stellar NFL career. He played three years for the Browns, and then was drafted by the Dallas Cowboys in the NFL expansion draft in 1960. He played for the Cowboys for eight productive years.

Clarke and Wooten’s presence on the CU team in 1956 was significant, but not just because they were good ballplayers. Following the season, their presence led the Colorado team to a crossroads. A decision had to be made. A stand had to be taken.

Revisiting The 1956 Orange Bowl

The American South was slowly, and reluctantly, emerging from segregation in 1956. But it was still under the shadow of Jim Crow Laws. The laws were many and varied. They banned black people from parts of restaurants, hotels, and public amenities that were reserved for white people. They also supported segregated schools and other public institutions. In 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested after sitting in the “whites only” section of a segregated public bus in Montgomery, Ala., then refusing to give up her seat to a white person. The following year, after a months-long bus boycott led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the U.S. Supreme Court compelled the city-owned transportation system in Montgomery to integrate its buses.

College football teams from the South, however, were not racially integrated in 1956. Colorado was matched against the Clemson Tigers in the Orange Bowl following the ’56 season. The game was to be played Jan. 1, 1957 in Miami.

But Clemson officials said its team would not play Colorado if Clarke and Wooten were on the field. Some in Miami Beach weren’t thrilled about the two black players’ presence either.

“Clemson was totally against playing against black players, but our whole team stood together, including the coaches, and said we will go as a team,” Wooten said.

As the story goes, Dal Ward told Clemson that CU would be there for the game, and he hoped Clemson would be there too, so the Buffs wouldn’t just have a scrimmage.

Franke Clarke |

Clemson’s attitude, though, was only part of the problem.

“Miami Beach was still segregated and the hotel personnel plainly stated they didn’t want any Negroes coming down there,” Wooten said. “When it became apparent that Colorado wasn’t going to back down, the Bal Harbor Hotel tried to reach a compromise. They said that Frank and I would have to stay in the same room and it would be on the top floor of the hotel. Frank and I had never roomed together. We roomed by position. My roommate was Bobby Salerno, and I didn’t want to change it. I can’t remember who Frank’s roommate was, but I know he felt the same way.

“We stood strong. When we went to Miami Beach, we had our usual roommates and it was business as usual. And Clemson did show up at the game and we beat them.”

When Wooten recalls the time, he does so with great emotion.

“It was a hectic time,” he said. “I have such great feeling for the stand my white teammates took and for the leadership of Jim Uhlir and Boyd Dowler. Man, what a lesson in human relationship.”

Wooten was no stranger to discrimination. The first time he experienced it in relation to football, there wasn’t a happy ending.

“It was in my sophomore year in high school in Carlsbad, New Mexico,” Wooten said. “I was the only black on the team. We were scheduled for a game in Texas and my school was asked not to bring me to the game. They said my life might be on the line. The school made the decision to leave me home. This hurt, but some of it was erased by what happened at Colorado.”

Another member of that 1956 Colorado team, John Bayuk, affectionately known as “The Beast,” remembers the situation from the side of some of CU’s white players.

Bayuk pulls no punches: “When Clemson said they wouldn’t play us, it was the wording that got to us. They said, ‘We’re not going to play with those monkeys.’ Then the hotel said that Frank and John would have to use the back door. We just said, ‘That’s a bunch of crap; if they can’t come with us wherever we go, then we’re not going.’ We laid it out. They are our teammates and they are with us.

“The hotel relented and guess what? Clemson said they would play the game.”

Bayuk said the off-the-field issues had an affect on the field.

“It made us play harder, I’ll tell you that,” Bayuk said. “We got up 20-0 on them, but they came back strong in the second half. One of the Clemson players later told me that their coach, Frank Howard, threatened to quit at half time. He said he was being embarrassed. It worked because they came back and got ahead of us 21-20, and they were driving again when Bob Stransky intercepted a pass. We moved it to the one-yard line and I was able to take it in for the winning touchdown.”

Bayuk said he was shocked by the furor.

Colorado's starting offense in the 1956 Orange Bowl anchored by Wooten (69 - second from right on the line. |

“I grew up in Salida, Colorado,” he said. “There was no segregation. My next-door neighbor was black and a terrific track athlete. We were good friends. At CU, Frank Clarke was very popular and was even elected Mr. CU by the student body.”

Wooten remembers hearing some ugly comments from people in the stands during the 1956 Orange Bowl. But both he and Bayuk agree the Clemson players never said anything racial or even referred to the talk leading up to the game.

Revisiting The 1961 Orange Bowl

By 1961, the Big Seven had become the Big Eight. The Buffaloes won the conference title and were to play another southern school — Louisiana State University. The same challenges arose.

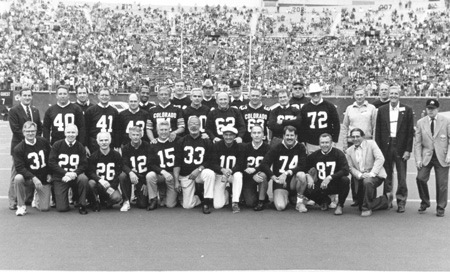

Through the years, discussions of these incidents have been pretty much on the back burner in Boulder. Many fans heard of the gut-wrenching decisions made by CU’s 1956 and 1961 teams for the first time at the Legends Banquet, hosted by the CU athletic department in the fall of 2006.

Bill Harris was a halfback on the 1961 team, and one of five African-American on the CU squad that season. He struck up a conversation with Wooten during the Legends Banquet. The 1956 team was celebrating its 50th anniversary that night, and Clarke and Wooten returned to the campus for the fete.

“I was talking to John Wooten and he was telling me the story of going to the Orange Bowl and it brought back memories of our own Orange Bowl team in 1961,” Harris said. “The parallels, five years apart, were astounding. I had tried to tell my story before, but could never get it out. After talking to John, I was determined to tell the story that night at the banquet and I finally got it out.”

And how. Choked up, with tears running down his face at the podium, there wasn’t a dry eye in the room, as the audience felt the pent-up emotion pouring from Harris. Not many in the room took notice of Wooten, the big offensive guard who blocked for Jim Brown, or Clarke, the end who caught 291 passes for 5,246 yards and 50 touchdowns for the Dallas Cowboys, openly weeping, as well.

Harris told the story of his 1961 Colorado team.

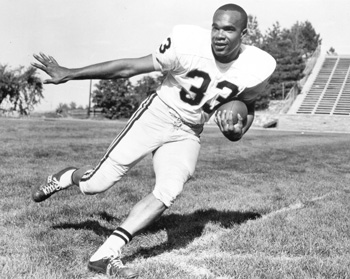

“Just as was the case with Wooten’s team, we had to beat Missouri to win the conference Championship and go to the Orange Bowl,” Harris said. “It was in Boulder and it was a hard-fought game. Late in the game, Missouri was leading 6-0 when we finally got something going. (CU quarterback) Gale Weidner called a pass play and things worked out that he threw the ball to me. I caught it and took it to the end zone for a touchdown. We got the extra point and won the game, 7-6.

Bill Harris caught a touchdown pass against Missouri that helped send the Buffaloes to the 1961 Orange Bowl. |

“The fans were throwing oranges on the field as we headed back to the locker room where the celebrating really started. The president of the university was there, the athletic director was there.

“We were all talking about the trip to Miami, and I’ll never forget the moment when the door at the back of the room opened and our captain, Joe Romig, accompanied by Charlie McBride, came in. They announced, ‘We are not going to the Orange Bowl.’

“The room grew quiet and they explained, ‘There appears to be racial problems and we will only go if we go as a team.’

“I had a feeling that is hard to describe,” Harris continued. “I looked at the other four black players and I could tell they were as overwhelmed with emotion as I was. That Joe and Chuck would stand up and say that and that all of the other white players on the team joined with them to take a stand for us. It was the greatest feeling in the world.”

The 1956 Post-Game Party

Back in 1956, even though Clarke and Wooten roomed with their normal roommates at the team hotel, and the game was played without unpleasantness on the field, there was one incident that bears repeating. Longtime CU historian Fred Casotti wrote about the post-game party for the Orange Bowl teams in his book “Football — CU Style.”

“The party was held at the Indian Creek Country Club in Miami Beach. Until January 1, 1957, no black had ever entered that club except as an employee. Clarke and Wooten were the first blacks to ever enter Indian Creek as guests. But Orange Bowl committee members urged (Coach Dal) Ward to ask the two men to leave as quickly as possible and even arranged for a prominent black Miami doctor to arrange for their entertainment once they had left the country club. Ward went along with the request and passed it on to the two players. They weren’t really excited about staying in a place that included 1948 Dixiecrat presidential candidate Strom Thurmond as a member of the welcoming line. So they went to the club and left as soon as the awards ceremony was over. And had a great time being shown much brighter parts of Miami Beach than Indian Creek Country Club. But time has a way of distorting incidents and by firing time in 1958, the story was that Ward personally kept these two players out of the club. Untrue? Completely! But it had an impact on the regential considerations which were to affect Ward’s life so drastically (when he was fired) in February of 1959.”

Ironic that this incident was used as a reason to fire Ward who had opened the door to African-American players when he brought in Clarke and Wooten.

Wooten remembers the country club incident well and said Casotti’s account is accurate.

“Frank and I didn’t have a problem with what happened that night,” Wooten said. “Back then, the Cotton Clubs were famous. The original in Harlem was so successful that they had opened Cotton Clubs all along the eastern seaboard. They featured high-class black entertainers, such as Cab Calloway. We had been to the Cotton Club and the King of Hearts Club in south Miami during bowl week, and honestly we had been trying to figure out how to get back to the Cotton Club that night after the game, so we jumped at the chance to get away. We were in a big hurry to get there.

“Rather than sit around the country club looking at people, we went out with that doctor and had a swinging good time.

“I’m sorry to hear that this story was distorted and used to help get Coach Ward fired. There is not one ounce of animosity as it relates to Coach Ward, or the CU family, about anything that happened in Miami. To say that he kept us out of the club is not only unfair, it is untrue. I was still on campus in 1958. Why didn’t somebody come and ask me?”

As to his relationship with Coach Ward, Wooten said, “I knew the entire Ward family. They are as good as I’ve ever known. Salerno and I used to spend time at their house. We even took care of some of the yard work and participated in church activities together.”

‘The Same Thing Happened To Us’

Harris was amazed to hear of the Indian Creek Country Club story. It sounded familiar.

“The same thing happened to us,” Harris said about the 1961 Orange Bowl post-game festivities. “The same place, the night after the game. Both teams were at the dinner and Sonny (Grandelius, CU’s head coach) told us that after the dinner we were free to go, to stay out of trouble, and be back to the hotel by curfew. There was absolutely no pressure on me or my black teammates to leave, but we couldn’t wait to get going. And you know what? There was a prominent black doctor waiting for us to provide transportation. And you know where he took us? The Cotton Club. We had a blast.”

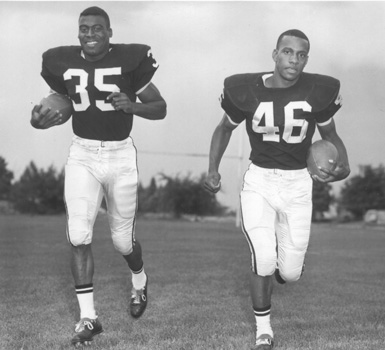

In 1961, the five African-Americans on the team were running back Teddy Woods from Pittsburgh, wide receiver Ed Coleman, from Carnegie, Penn., running back Noble Milton, from Herminie, Penn., tackle Al Hollingsworth from Omaha, Neb., and Harris, from Hackensack, N.J.

Joe Romig, a two-time All-American, a member of the Big Eight and College Football Halls of Fame, and a Rhodes Scholar, was the 1961 captain. He is the living link between the 1956 and 1961 teams.

“I came to Colorado in 1958 from Lakewood High School, and John Wooten was on the team,” Romig said. “In our scrimmages, I was fodder for him.”

Head Coach Dal Ward |

Romig said going up against a black teammate was never an issue.

“My high school coach, Tom Hancock, during wrestling season, used to have us work out with the top wrestlers in the area,” Romig said. “One was Marvin Oliver from Manual High School in Denver. It made absolutely no difference that he was black. He came to Colorado and was a tough 220-pound fullback.

“At CU there never was a perception of color or ethnic lines. We didn’t have an athletic dorm, but during preseason drills we did live together. We slept, showered and ate with each other. We won together and we lost together. We were a team.

“When it came to the Orange Bowl, we made it quite clear that we would go as a team and not split up into different hotels. If the hotel said our black teammates had to stay somewhere else, well, we would go to that hotel and stay with them. Coach Grandelius and the coaching staff backed us one hundred percent.”

LSU had won the national championship three years before and still had a talent-laden team in 1961. The legendary Paul Dietzel was coach of the Tigers. He said playing a Colorado team that had black players on its roster was never an issue with his football team. The talk came from the university officials.

That’s the way Romig understood it.

“From what I heard, it was the political climate in Louisiana and the hotel managers, who were the problems,” Romig said.

In fact, it was against LSU school policy for its white athletes to play against a team that had black athletes at the time.

“The LSU Board of Supervisors had to meet and change the (university) rules so that we could play against a black player,” Dietzel said.

On The Field In 1961

So what was the feeling on the field that day in 1961?

“Those guys played straight football,” Harris recalled of the matchup with the LSU Tigers. “There’s always trash talk going on on the field. Yeah, that was going on, but it was not racial. It was just a hard-fought, good football game.

“At the beginning, Teddy Woods and I were the kickoff return men. Teddy was a real speedster. He ran the hundred-yard dash in something like 9.5 seconds. Anyway, it was the opening kickoff and we were standing in the end zone just in front of the LSU band and they were playing Dixieand the fans were yelling and screaming at us.

“Teddy had these eyes that were just big buttons. I looked over at Teddy and his eyes were wide open. He said, ‘Let’s move up a little bit,’ so we moved up to the goal line and the ball came. Teddy said, ‘Bill, you take it, you take it.’ I did and fumbled the opening kickoff of the Orange Bowl. We played them tough for a half and trailed by four points, but eventually ‘the Chinese Bandits’ (LSU’s infamous defense) rocked us. We just couldn’t do anything on offense that day.”

LSU beat the Buffaloes 25-7. Romig’s memories are similar.

Halfbacks Ted Woods (35) and Ed Coleman (46) in 1961 |

“Honestly, I think we over practiced,” Romig said. “We were really flat. They were a great team. There was never a racial incident and the two teams got to spend time together after the game. The two teams had a joint dinner the night of the bowl game. Several of the LSU players came to me and said, ‘We really like your black players, they are real gentlemen. We’re really sorry about all that stuff that came out of Baton Rouge.’”

Harris said players from the two teams even spent more time together the next day when they all went on a fishing trip.

“The LSU players couldn’t have been nicer,” he said.

Later, Harris and Woods were teammates in the Canadian Football League with the Calgary Stampeders.

“I had been with Ottawa and when I came to Calgary, in one of the first team meetings, Teddy said to look across the room, ”Harris recalled. “I said, ‘’What’s up?’

“He said, ‘Those two guys over there played at LSU and played against us.’ Teddy called them over and we had a good conversation. They said again that the team wasn’t involved in all that talk, it was the political stuff going on in Louisiana.”

Grandelius’ exit

There’s still more to the story of that 1961 team that went 9-1 during the regular season and won the Big Eight Championship. No other CU team before had won nine games. During the season, rumors began to circulate that Colorado was being investigated by the NCAA. The rumors were rampant in the days leading up to the Orange Bowl and despite the successful season, Grandelius was fired.

CU Buffalo historian Fred Casotti explained it this way: “Sonny’s biggest shortcoming was his impatience. He was a young man in a hurry. At Colorado, he stepped on some toes — of some administrators and other coaches around the nation. …The CU administration by now was frightened, almost horrified, by the machine that Sonny was establishing, as he had been directed to by them, decided it was time to be rid of this All-American boy, who, to them, had taken on some of the characteristics of Attila the Hun. They appointed their own investigator to supplement the NCAA’s. And so when the fairly modest charges were proven….Sonny got fired. Coldly and mercilessly and almost jubilantly.”

The firing and investigation had rocked the CU football program and the alumni director Bud Davis, who had been an assistant on Ward’s staff, was named head coach. In the middle of spring practice, the NCAA handed down its verdict: CU was given a two-year probation, during which it was not allowed to play in any bowl games and was banned from televised games. The NCAA named 21 players, 12 of whom were seniors in 1961, as having received illegal financial assistance and transportation. A month later the Big Eight suspended the nine remaining underclassman for a year, and the university suspended six more.

Playing Alabama in 1969

It took CU four years to recover. The record each year in 1962, ‘63, and ‘64 was 2-8. Davis coached only one year and, in 1963, was replaced by Eddie Crowder, who was charged with leading Colorado football back to respectability. It took until 1967, when the Buffs went 9-2 and were back in the bowl business with a win over Miami in the Bluebonnet Bowl.

While there appeared to be no racial overtones connected with that game in Houston, two years later, at the 1969 Liberty Bowl, when Colorado played Alabama, race issues again raised their ugly head. The Crimson Tide never threatened not to play the game. But the site was Memphis, Tenn., in the Deep South and Alabama had no black players on its team. CU’s black players were subjected to racial remarks and abuse from fans before the game. The CU players wanted to make a statement and appointed tackle Bill Collins, an African-American, as the game captain.

All-American and Hall of Famer, Bobby Anderson, said, “We wanted Bill to represent us, because we wanted to make a point to Alabama. Some of their fans were yelling racial epithets.”

Colorado won that game 47-33. Coach Crowder called it “one of the best victories we ever had.”

Legendary Alabama Coach Paul “Bear” Bryant had already decided to recruit black players and the color barrier was broken in Tuscaloosa in 1971, the same year that LSU had its first black player on the roster.

Harris remembers talking to Anderson about the 1969 game and although the situation was different, Harris said once again the white players really supported their black teammates.

Harris (33) organizes reunions, like this one of the 1961 Orange Bowl team, as CU's Alumni C Club Director |

Five Decades Later

Harris has been the director of Colorado’s Alumni C-Club the past seven years. When the Buffs played Alabama in the Independence Bowl in Shreveport, La., in 2007, he was there. It was a time to take note of changes that have occurred the past 47 years.

“Alabama had as many black players as did Colorado,” Harris said. “At that bowl game, I invited Mary Mothershed, who was the first black homecoming queen at CU (in 1962), to sit with me. We sat and talked about those experiences, her experiences, and agreed, ‘Here we are playing against Alabama after all these years and how things have really, really come together.’”

Harris reflected further: “It was a different time. I’m just so happy to see that things have progressed in the area of racial relations. You know, this might be a surprise, but I wouldn’t change a thing. I was happy to have experienced all of that.”

Wooten has similar feelings.

“I look back on my life, and I can see how things have changed,” Wooten said. “Look what’s going on in the NFL. I’ve been involved with the NFL over the years, working with Steelers’ owner Dan Rooney on the diversity committee. With the help of other owners we have changed the hiring polices and pushed and pulled the NFL into more minority hires.

“I have grown and learned over the years and I have, in my lifetime, seen this country go from segregation to what it is today.”

After working for many years in the scouting departments for the Dallas Cowboys and Philadelphia Eagles, Wooten is still active as a football consultant. His 1956 teammate, Frank Clarke, is involved in health care in North Carolina.

It’s interesting to note the careers of the black members of the 1961 team. Before helming CU’s Alumni C-Club, Harris worked in healthcare administration in New Jersey for two decades. Woods is a practicing attorney. Milton is an executive with Beatrice Foods in New Jersey. Coleman is a healthcare administrator in San Francisco. Hollingsworth is the founder, president and CEO of a company in southern California that trains leaders. He and his wife purchased the Ponderosa Ranch, made famous in the television series “Bonanza”.

The Right Thing

Both the 1956 and 1961 teams wrote a special chapter in the history of Colorado football and it is comforting to know it was recognized at the time by at least one member of the media. It is a strange twist and a fitting ending to this story.

Joe Romig and his wife Barbara were attending a reunion of the American Oxford Club and Rhodes Scholars in New York in early April of this year. While Joe went to a breakfast with the group, Barbara took leave to attend mass because it was Greek Independence Day, and being of Greek heritage, she thought this was a good way to celebrate. She sat next to a gentleman, who used two canes and had trouble walking. After mass, they struck up a conversation on the way out of the church, and she mentioned that her name was Romig and she was from Boulder, Colo.

“He asked, if by chance, I was related to the great football player from the University of Colorado, Joe Romig,” Barbara said. “I said, ‘Yes, he is my husband.’

“He then told me that he was a retired sportswriter and that he wrote a syndicated column in the days when Joe played. He covered the Big Eight and covered that Orange Bowl game.

“He said, ‘Here was Colorado playing against a big Southeastern Conference team and they lost the game, but they won something far more valuable. Your husband and that CU team made a stand against the Old South. They stood together as a team with no color lines. They stood for what was right.’”

After all those years, the sportswriter still remembered.